Great Beards No 1 (O my Hornby and my Barlow)

No 1 - John Taylor, 1971 (and sadly I can't find a picture)

As schoolboys, my friends and I got cheap tickets for international rugby matches at Murrayfield. Scotland weren't doing very well, and in fact I had never seen them win (well, I'd only been watching for two years) at the time of the match against the mighty Welsh in 1971. It was a wonderful match: the lead changed hands many times, and Scotland were leading 18-14 in the last minute. But Gerald Davies scored a fine try near the corner (18-17), and the bearded flanker John Taylor had the opportunity to convert the try. He did so - a splendid kick, Wales won 19-18 and we went home disappointed. In retrospect, what a wonderful Welsh side it was - with J.P.R. Williams, Gareth Edwards, Mervyn Davies and my hero the great Barry John. What a privilege to see that match!

John Taylor risked his career shortly afterwards, if my memory is correct, by refusing selection for the British Lions tour to South Africa for political reasons. I was just beginning to take an interest in politics at the time and I admired him for that.

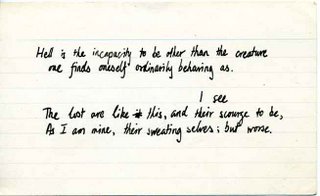

Though my own red roses there may blow;

It is little I repair to the matches of the Southron folk,

Though the red roses crest the caps, I know.

For the field is full of shades as I near a shadowy coast,

And a ghostly batsman plays to the bowling of a ghost,

And I look through my tears on a soundless-clapping host

As the run stealers flicker to and fro,

To and fro:

O my Hornby and my Barlow long ago !